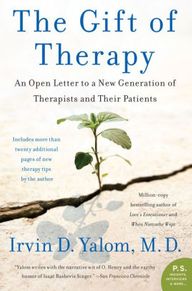

44. The Gift of Therapy - Irvin D. Yalom (📱)

27 Sep 2018

Reading Notes:

One of our chief modes of death denial is a belief in personal specialness, a conviction that we are exempt from biological necessity and that life will not deal with us in the same harsh way it deals with everyone else.

Erik Erikson, in his study of the life cycle, described this late-life stage as generativity, a post-narcissism era when attention turns from expansion of oneself toward care and concern for succeeding generations.

When I see patients in group therapy I work from an interpersonal frame of reference and make the assumption that patients fall into despair because of their inability to develop and sustain gratifying interpersonal relationships.

However, when I operate from an existential frame of reference, I make a very different assumption: patients fall into despair as a result of a confrontation with harsh facts of the human condition—the “givens” of existence. Since many of the offerings in this book issue from an existential framework that is unfamiliar to many readers, a brief introduction is in order.

Definition of existential psychotherapy: Existential psychotherapy is a dynamic therapeutic approach that focuses on concerns rooted in existence.

The most useful book I read was Karen Horney’s Neurosis and Human Growth. And the single most useful concept in that book was the notion that the human being has an inbuilt propensity toward self-realization. If obstacles are removed, Horney believed, the individual will develop into a mature, fully realized adult, just as an acorn will develop into an oak tree.

My task was to remove obstacles blocking my patient’s path. I did not have to do the entire job; I did not have to inspirit the patient with the desire to grow, with curiosity, will, zest for life, caring, loyalty, or any of the myriad of characteristics that make us fully human. No, what I had to do was to identify and remove obstacles.

Though diagnosis is unquestionably critical in treatment considerations for many severe conditions with a biological substrate (for example, schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, major affective disorders, temporal lobe epilepsy, drug toxicity organic or brain disease from toxins, degenerative causes, or infectious agents), diagnosis is often counterproductive in the everyday psychotherapy of less severely impaired patients.

Everyone—and that includes therapists as well as patients—is destined to experience not only the exhilaration of life, but also its inevitable darkness: disillusionment, aging, illness.

We are like lambs in the field, disporting themselves under the eyes of the butcher, who picks out one first and then another for his prey. So it is that in our good days we are all unconscious of the evil that Fate may have presently in store for us—sickness, poverty, mutilation, loss of sight or reason.

I prefer to think of my patients and myself as fellow travelers, a term that abolishes distinctions between “them” (the afflicted) and “us” (the healers).

We are all in this together and there is no therapist and no person immune to the inherent tragedies of existence.

Rilke’s letters to a young poet in which he advises, “Have patience with everything unresolved and try to love the questions themselves.”

What do patients recall when they look back, years later, on their experience in therapy? Answer: Not insight, not the therapist’s interpretations. More often than not, they remember the positive supportive statements of their therapist. I make a point of regularly expressing my positive thoughts and feelings about my patients, along a wide range of attributes—for example, their social skills, intellectual curiosity, warmth, loyalty to their friends, articulateness, courage in facing their inner demons, dedication to change, willingness to self-disclose, loving gentleness with their children, commitment to breaking the cycle of abuse, and decision not to pass on the “hot potato” to the next generation

Acceptance and support from one who knows you so intimately is enormously affirming.

A lovely example of a reframed comment that provided much comfort to me occurred some time ago when I expressed my disappointment at a bad review of one of my books to a friend, William Blatty, the author of The Exorcist. He responded in a wonderfully supportive manner, which instantaneously healed my wound. “Irv, of course you’re upset by the review. Thank God for it! If you weren’t so sensitive, you wouldn’t be such a good writer.”

Fifty years ago Carl Rogers identified “accurate empathy” as one of the three essential characteristics of the effective therapist (along with “unconditional positive regard” and “genuineness”) and launched the field of psychotherapy research, which ultimately marshaled considerable evidence to support the effectiveness of empathy.

Young therapists must work through their own neurotic issues; they must learn to accept feedback, discover their own blind spots, and see themselves as others see them; they must appreciate their impact upon others and learn how to provide accurate feedback.

There are times when my patients lament the inequality of the psychotherapy situation. They think about me far more than I think about them. I loom far larger in their lives than they do in mine. If patients could ask any question they wished, I am certain that, for many, that question would be: Do you ever think about me?

“I know it feels unfair and unequal for you to be thinking of me more than I of you, for you to be carrying on long conversations with me between sessions, knowing that I do not similarly speak in fantasy to you. But that’s simply the nature of the process. I had exactly the same experience during my own time in therapy, when I sat in the patient’s chair and yearned to have my therapist think more about me.”

Our self-image is formulated to a large degree upon the reflected appraisals we perceive in the eyes of the important figures in our life.

Each individual has a different internal world and the stimulus has a different meaning to each.

A goal of therapy is to increase reality testing and to help individuals see themselves as others see them.

Perhaps I can help you understand what goes wrong with relationships in your life by examining our relationship as it is occurring.

It is hardly possible for the patient to reject this offer, and once we have nailed down this contract, I feel bolder and less intrusive when giving feedback.

To a despondent or suicidal patient: “I understand that you feel deeply discouraged, that at times you feel like giving up, that right now you even feel like taking your life. But you are nonetheless here today. Some part of you has brought the rest of you into my office. Now, please, I want to talk to that part of you—the part that wants to live.”

Though the physicality of death destroys us, the idea of death may save us.

As long as patients persist in believing that their major problems are a result of something outside their control—the actions of other people, bad nerves, social class injustices, genes—then we therapists are limited in what we can offer.

Leaping in to make decisions for patients is a good way to lose them. Patients assigned a task that they cannot or will not perform are unhappy patients.

Sometimes I simply remind patients that sooner or later they will have to relinquish the goal of having a better past.

“Don’t try to leave that space. Stay with it. Please keep talking to me; try to put your feelings into words.” Or you may ask a question I often use: “If your tears had a voice, what would they be saying?”

Therapists place a far higher value than patients on interpretation and insight. We therapists grossly overvalue the content of the intellectual treasure hunt;

Bear in mind Nietzsche’s dictum: “There is no truth, there is only interpretation.”

The closeness of the therapy relationship serves many purposes. It affords a safe place for patients to reveal themselves as fully as possible. More than that, it offers them the experience of being accepted and understood after deep disclosure. It teaches social skills: The patient learns what an intimate relationship requires. And the patient learns that intimacy is possible, even achievable.

Patients regularly develop feelings of love and/or sexual feelings for their therapist. The dynamics of such positive transference are often overdetermined. For one thing, patients are exposed to a very rare, gratifying, and delicious situation. Their every utterance is examined with interest, every event of their past and present life is explored, they are nurtured, cared for, and unconditionally accepted and supported.

Keep in mind that the feelings arising in the therapy situation generally belong more to the role than the person: Do not mistake the transferential adoration as a sign of your irresistible personal attractiveness or charm.

I do not like to work with patients who are in love. Perhaps it is because of envy—I too crave enchantment. Perhaps it is because love and psychotherapy are fundamentally incompatible. The good therapist fights darkness and seeks illumination, while romantic love is sustained by mystery and crumbles upon inspection. I hate to be love’s executioner.

Erich Fromm’s timeless monograph, The Art of Loving.

Sooner or later I hope to arrive at the question: What would you be thinking about if you were not obsessed with . . . ?

Too often, we therapists neglect our personal relationships. Our work becomes our life. At the end of our workday, having given so much of ourselves, we feel drained of desire for more relationship. Besides, patients are so grateful, so adoring so idealizing, we therapists run the risk of becoming less appreciative of family members and friends, who fail to recognize our omniscience and excellence in all things.

Still others sadden me as I witness how an entire life can be needlessly consumed by shame and the inability to forgive oneself.

Those who are cradlers of secrets are granted a clarifying lens through which to view the world—a view with less distortion, denial, and illusion, a view of the way things really are.

When I turn to others with the knowledge that we are all (therapist and patient alike) burdened with painful secrets— guilt for acts committed, shame for actions not taken, yearnings to be loved and cherished, deep vulnerabilities,insecurities, and fears—I draw closer to them. Being a cradler of secrets has, as the years have passed, made me gentler and more accepting.

Not only does our work provide us the opportunity to transcend ourselves, to evolve and to grow, and to be blessed by a clarity of vision into the true and tragic knowledge of the human condition, but we are offered even more.

We are intellectually challenged. We become explorers immersed in the grandest and most complex of pursuits—the development and maintenance of the human mind. Hand in hand with patients, we savor the pleasure of great discoveries— the “aha” experience when disparate ideational fragments suddenly slide smoothly together into coherence.