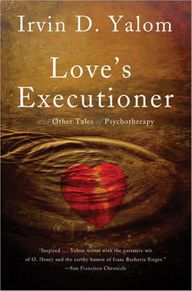

47. Love's Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy - Irwin D. Yalom (📱)

13 Nov 2018

Reading Notes:

Many things—a simple group exercise, a few minutes of deep reflection, a work of art, a sermon, a personal crisis, a loss—remind us that our deepest wants can never be fulfilled: our wants for youth, for a halt to aging, for the return of vanished ones, for eternal love, protection, significance, for immortality itself. It is when these unattainable wants come to dominate our lives that we turn for help to family, to friends, to religion—sometimes to psychotherapists.

A nightmare is a failed dream, a dream that, by not “handling” anxiety, has failed in its role as the guardian of sleep.

Every therapist knows that the crucial first step in therapy is the patient’s assumption of responsibility for his or her life predicament. As long as one believes that one’s problems are caused by some force or agency outside oneself, there is no leverage in therapy. If, after all, the problem lies out there, then why should one change oneself?

I focus on what is going on at the moment between a patient and me rather than on the events of his or her past or current life.

it is extraordinarily hard, even terrifying, to own the insight that you and only you construct your own life design.

“Countertransference.”

Nietszche said, “The final reward of the dead—to die no more.”

Patients, like everyone else, profit most from a truth they, themselves, discover.

I had come to believe that the fear of death is always greatest in those who feel that they have not lived their life fully. A good working formula is: the more unlived life, or unrealized potential, the greater one’s death anxiety.

(We are all stuck with some anxiousness about death. It’s the price of admission to self-awareness.)

One of the axioms of psychotherapy is that the important feelings one has for another always get communicated through one channel or another—if not verbally, then nonverbally.

her “I never thought it would happen to me” reflecting the loss of belief in her personal specialness.

It is wildly improbable that the receiver’s image will match the sender’s original mental image.

We pack the physical outline of the creature we see with all the ideas we already formed about him, and in the complete picture of him which we compose in our minds, those ideas have certainly the principal place. In the end they come to fill out so completely the curve of his cheeks, to follow so exactly the line of his nose, they blend so harmoniously in the sound of his voice that these seem to be no more than a transparent envelope, so that each time we see the face or hear the voice it is our own ideas of him which we recognize and to which we listen.

“Each time we see the face . . . it is our own ideas of him which we recognize”—these words provide a key to understanding many miscarried relationships.

Nietzsche who said somewhere that when you first meet someone, you know all about him; on subsequent meetings, you blind yourself to your own wisdom.

If we relate to people believing that we can categorize them, we will neither identify nor nurture the parts, the vital parts, of the other that transcend category. The enabling relationship always assumes that the other is never fully knowable.

A comment stating that the therapist has been thinking about the patient outside of their scheduled hour has never, in my experience, failed to galvanize the latter’s interest.

My old teacher, John Whitehorn, taught me that one can diagnose “psychosis” by the character of the therapeutic relationship: the patient, he suggested, should be considered “psychotic” if the therapist no longer has any sense that he and the patient are allies who are working together to improve the patient’s mental health.

No, a therapist helps a patient not by sifting through the past but by being lovingly present with that person; by being trustworthy, interested; and by believing that their joint activity will ultimately be redemptive and healing.

As he was flipping through a copy of Psychology Today in a dentist’s office, he was intrigued by an article suggesting that one attempt to construct a final, meaningful conversation with each of the important vanished people in one’s life.

an established school of thought, a professional home such as a Freudian, a Jungian, a Lacanian, an Adlerian, or a cognitive-behavioral one with an all-embracing explanatory system.

Existential Psychotherapy , intending not to establish a new field but to make all therapists more aware of existential issues. Four major existential concerns—death, meaning in life, isolation, and freedom—play a crucial role in the inner life of every human being

It did not escape me that the ideas of some of the most important existential thinkers—for example, Camus and Sartre—are most vivid and compelling in their stories and novels rather than in technical philosophic works.