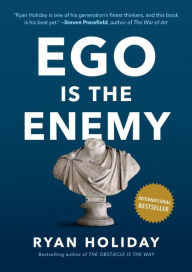

5. Ego is the Enemy - Ryan Holiday (📱)

06 Feb 2017

rating 9.5/10

Reading Notes:

The ego we see most commonly goes by a more casual definition: an unhealthy belief in our own importance. Arrogance. Self-centered ambition.

The performance artist Marina Abramović puts it directly: “If you start believing in your greatness, it is the death of your creativity.”

Sherman had a good rule he tried to observe. “Never give reasons for you what think or do until you must. Maybe, after a while, a better reason will pop into your head.”

The power of being a student is not just that it is an extended period of instruction, it also places the ego and ambition in someone else’s hands.

The mixed martial arts pioneer and multi-title champion Frank Shamrock has a system he trains fighters in that he calls plus, minus, and equal. Each fighter, to become great, he said, needs to have someone better that they can learn from, someone lesser who they can teach, and someone equal that they can challenge themselves against.

A true student is like a sponge. Absorbing what goes on around him, filtering it, latching on to what he can hold. A student is self-critical and self-motivated, always trying to improve his understanding so that he can move on to the next topic, the next challenge. A real student is also his own teacher and his own critic. There is no room for ego there.

The old proverb says, “When student is ready, the teacher appears.”

What humans require in our ascent is purpose and realism. Purpose, you could say, is like passion with boundaries. Realism is detachment and perspective.

It’d be far better if you were intimidated by what lies ahead—humbled by its magnitude and determined to see it through regardless.

Find canvases for other people to paint on. Be an anteambulo. Clear the path for the people above you and you will eventually create a path for yourself.

Be lesser, do more. Imagine if for every person you met, you thought of some way to help them, something you could do for them? And you looked at it in a way that entirely benefited them and not you. The cumulative effect this would have over time would be profound: You’d learn a great deal by solving diverse problems. You’d develop a reputation for being indispensable. You’d have countless new relationships. You’d have an enormous bank of favors to call upon down the road.

A proud man is always looking down on things and people; and, of course, as long as you are looking down, you cannot see something that is above you. —C. S. LEWIS

Pride takes a minor accomplishment and makes it feel like a major one.

The famous conqueror and warrior Genghis Khan groomed his sons and generals to succeed him later in life, he repeatedly warned them, “If you can’t swallow your pride, you can’t lead.” He told them that pride would be harder to subdue than a wild lion. He liked the analogy of a mountain. He would say, “Even the tallest mountains have animals that, when they stand on it, are higher than the mountain.”

“The first product of self-knowledge is humility,” Flannery O’Connor once said. This is how we fight the ego, by really knowing ourselves.

The question to ask, when you feel pride, then, is this: What am I missing right now that a more humble person might see? What am I avoiding, or running from, with my bluster, franticness, and embellishments? It is far better to ask and answer these questions now, with the stakes still low, than it will be later.

It isn’t “Don’t boast about what hasn’t happened yet.” It is more directly “Don’t boast.” There’s nothing in it for you.

“You can’t build a reputation on what you’re going to do,” was how Henry Ford put it.

To be both a craftsman and an artist. To cultivate a product of labor and industry instead of just a product of the mind. It’s here where abstraction meets the road and the real, where we trade thinking and talking for working. Every time you sit down to work, remind yourself: I am delaying gratification by doing this. I am passing the marshmallow test. I am earning what my ambition burns for. I am making an investment in myself instead of in my ego. Give yourself a little credit for this choice, but not so much, because you’ve got to get back to the task at hand: practicing, working, improving.

“Man is pushed by drives,” Viktor Frankl observed. “But he is pulled by values.”

The physicist John Wheeler, who helped develop the hydrogen bomb, once observed that “as our island of knowledge grows, so does the shore of our ignorance.”

As we first succeed, we will find ourselves in new situations, facing new problems. The freshly promoted soldier must learn the art of politics. The salesman, how to manage. The founder, how to delegate. The writer, how to edit others. The comedian, how to act. The chef turned restaurateur, how to run the other side of the house.

With accomplishment comes a growing pressure to pretend that we know more than we do. To pretend we already know everything. Scientia infla (knowledge puffs up). That’s the worry and the risk—thinking that we’re set and secure, when in reality understanding and mastery is a fluid, continual process. To know what you like is the beginning of wisdom and of old age. —ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON

All of us regularly say yes unthinkingly, or out of vague attraction, or out of greed or vanity. Because we can’t say no—because we might miss out on something if we did. We think “yes” will let us accomplish more, when in reality it prevents exactly what we seek. All of us waste precious life doing things we don’t like, to prove ourselves to people we don’t respect, and to get things we don’t want.

According to Seneca, the Greek word euthymia is one we should think of often: it is the sense of our own path and how to stay on it without getting distracted by all the others that intersect it. In other words, it’s not about beating the other guy. It’s not about having more than the others. It’s about being what you are, and being as good as possible at it, without succumbing to all the things that draw you away from it. It’s about going where you set out to go. About accomplishing the most that you’re capable of in what you choose. That’s it. No more and no less. (By the way, euthymia means “tranquillity” in English.)

If I am not for myself who will be for me? If I am only for myself, who am I? —HILLEL

To borrow from Aristotle again, what’s difficult is to apply the right amount of pressure, at the right time, in the right way, for the right period of time, in the right car, going in the right direction.

As Goethe once observed, the great failing is “to see yourself as more than you are and to value yourself at less than your true worth.”

Humble and strong people don’t have the same trouble with these troubles that egotists do. There are fewer complaints and far less self-immolation. Instead, there’s stoic—even cheerful—resilience. Pity isn’t necessary. Their identity isn’t threatened. They can get by without constant validation.

This is what we’re aspiring to—much more than mere success. What matters is that we can respond to what life throws at us. And how we make it through.

Acording to Greene, there are two types of time in our lives: dead time, when people are passive and waiting, and alive time, when people are learning and acting and utilizing every second. Every moment of failure, every moment or situation that we did not deliberately choose or control, presents this choice: Alive time. Dead time.

That’s what so many of us do when we fail or get ourselves into trouble. Lacking the ability to examine ourselves, we reinvest our energy into exactly the patterns of behavior that caused our problems to begin with.

John Wooden’s advice to his players says it: Change the definition of success. “Success is peace of mind, which is a direct result of self-satisfaction in knowing you made the effort to do your best to become the best that you are capable of becoming.”

“Ambition,” Marcus Aurelius reminded himself, “means tying your well-being to what other people say or do . . . Sanity means tying it to your own actions.”

In fact, many significant life changes come from moments in which we are thoroughly demolished, in which everything we thought we knew about the world is rendered false. We might call these “Fight Club moments.” Sometimes they are self-inflicted, sometimes inflicted on us, but whatever the cause they can be catalysts for changes we were petrified to make.

It can ruin your life only if it ruins your character. —MARCUS AURELIUS

Let’s say you’ve failed and let’s even say it was your fault. Shit happens and, as they say, sometimes shit happens in public. It’s not fun. The questions remain: Are you going to make it worse? Or are you going to emerge from this with your dignity and character intact? Are you going to live to fight another day?

If your reputation can’t absorb a few blows, it wasn’t worth anything in the first place.

I never look back, except to find out about mistakes . . . I only see danger in thinking back about things you are proud of. —ELISABETH NOELLE-NEUMANN

“Vain men never hear anything but praise.”

For us, the scoreboard can’t be the only scoreboard. Warren Buffett has said the same thing, making a distinction between the inner scorecard and the external one. Your potential, the absolute best you’re capable of—that’s the metric to measure yourself against. Your standards are. Winning is not enough. People can get lucky and win. People can be assholes and win. Anyone can win. But not everyone is the best possible version of themselves.

And why should we feel anger at the world? As if the world would notice! —EURIPIDES

As Harold Geneen put it, “People learn from their failures. Seldom do they learn anything from success.”

It’s why the old Celtic saying tells us, “See much, study much, suffer much, that is the path to wisdom.”

Aspiration leads to success (and adversity). Success creates its own adversity (and, hopefully, new ambitions). And adversity leads to aspiration and more success. It’s an endless loop.

Perhaps it is like Plutarch’s reflection that we don’t “so much gain the knowledge of things by the words, as words by the experience [we have] of things.”